Optimizing Performance

Internally, React uses several clever techniques to minimize the number of costly DOM operations required to update the UI. For many applications, using React will lead to a fast user interface without doing much work to specifically optimize for performance. Nevertheless, there are several ways you can speed up your React application.

Use The Production Build #

If you're benchmarking or experiencing performance problems in your React apps, make sure you're testing with the minified production build:

- For Create React App, you need to run

npm run buildand follow the instructions. - For single-file builds, we offer production-ready

.min.jsversions. - For Browserify, you need to run it with

NODE_ENV=production. - For Webpack, you need to add this to plugins in your production config:

new webpack.DefinePlugin({

'process.env': {

NODE_ENV: JSON.stringify('production')

}

}),

new webpack.optimize.UglifyJsPlugin()

- For Rollup, you need to use the replace plugin before the commonjs plugin so that development-only modules are not imported. For a complete setup example see this gist.

plugins: [

require('rollup-plugin-replace')({

'process.env.NODE_ENV': JSON.stringify('production')

}),

require('rollup-plugin-commonjs')(),

// ...

]

The development build includes extra warnings that are helpful when building your apps, but it is slower due to the extra bookkeeping it does.

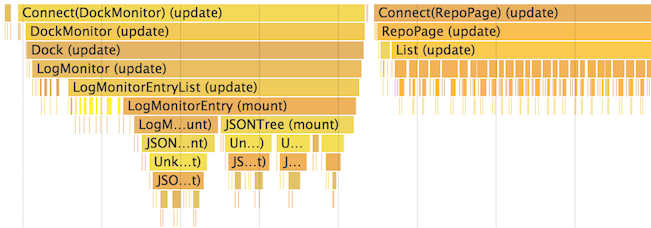

Profiling Components with Chrome Timeline #

In the development mode, you can visualize how components mount, update, and unmount, using the performance tools in supported browsers. For example:

To do this in Chrome:

Load your app with

?react_perfin the query string (for example,http://localhost:3000/?react_perf).Open the Chrome DevTools Timeline tab and press Record.

Perform the actions you want to profile. Don't record more than 20 seconds or Chrome might hang.

Stop recording.

React events will be grouped under the User Timing label.

Note that the numbers are relative so components will render faster in production. Still, this should help you realize when unrelated UI gets updated by mistake, and how deep and how often your UI updates occur.

Currently Chrome, Edge, and IE are the only browsers supporting this feature, but we use the standard User Timing API so we expect more browsers to add support for it.

Avoid Reconciliation #

React builds and maintains an internal representation of the rendered UI. It includes the React elements you return from your components. This representation lets React avoid creating DOM nodes and accessing existing ones beyond necessity, as that can be slower than operations on JavaScript objects. Sometimes it is referred to as a "virtual DOM", but it works the same way on React Native.

When a component's props or state change, React decides whether an actual DOM update is necessary by comparing the newly returned element with the previously rendered one. When they are not equal, React will update the DOM.

In some cases, your component can speed all of this up by overriding the lifecycle function shouldComponentUpdate, which is triggered before the re-rendering process starts. The default implementation of this function returns true, leaving React to perform the update:

shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps, nextState) {

return true;

}

If you know that in some situations your component doesn't need to update, you can return false from shouldComponentUpdate instead, to skip the whole rendering process, including calling render() on this component and below.

shouldComponentUpdate In Action #

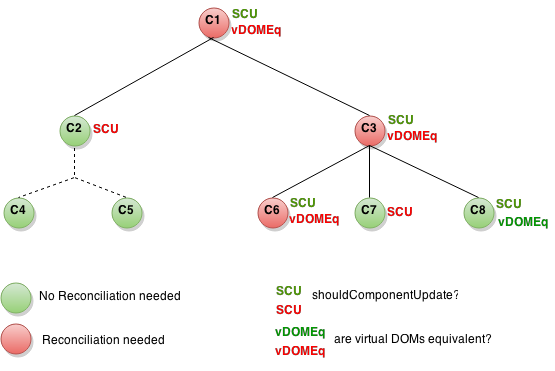

Here's a subtree of components. For each one, SCU indicates what shouldComponentUpdate returned, and vDOMEq indicates whether the rendered React elements were equivalent. Finally, the circle's color indicates whether the component had to be reconciled or not.

Since shouldComponentUpdate returned false for the subtree rooted at C2, React did not attempt to render C2, and thus didn't even have to invoke shouldComponentUpdate on C4 and C5.

For C1 and C3, shouldComponentUpdate returned true, so React had to go down to the leaves and check them. For C6 shouldComponentUpdate returned true, and since the rendered elements weren't equivalent React had to update the DOM.

The last interesting case is C8. React had to render this component, but since the React elements it returned were equal to the previously rendered ones, it didn't have to update the DOM.

Note that React only had to do DOM mutations for C6, which was inevitable. For C8, it bailed out by comparing the rendered React elements, and for C2's subtree and C7, it didn't even have to compare the elements as we bailed out on shouldComponentUpdate, and render was not called.

Examples #

If the only way your component ever changes is when the props.color or the state.count variable changes, you could have shouldComponentUpdate check that:

class CounterButton extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {count: 1};

}

shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps, nextState) {

if (this.props.color !== nextProps.color) {

return true;

}

if (this.state.count !== nextState.count) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

render() {

return (

<button

color={this.props.color}

onClick={() => this.setState(state => ({count: state.count + 1}))}>

Count: {this.state.count}

</button>

);

}

}

In this code, shouldComponentUpdate is just checking if there is any change in props.color or state.count. If those values don't change, the component doesn't update. If your component got more complex, you could use a similar pattern of doing a "shallow comparison" between all the fields of props and state to determine if the component should update. This pattern is common enough that React provides a helper to use this logic - just inherit from React.PureComponent. So this code is a simpler way to achieve the same thing:

class CounterButton extends React.PureComponent {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {count: 1};

}

render() {

return (

<button

color={this.props.color}

onClick={() => this.setState(state => ({count: state.count + 1}))}>

Count: {this.state.count}

</button>

);

}

}

Most of the time, you can use React.PureComponent instead of writing your own shouldComponentUpdate. It only does a shallow comparison, so you can't use it if the props or state may have been mutated in a way that a shallow comparison would miss.

This can be a problem with more complex data structures. For example, let's say you want a ListOfWords component to render a comma-separated list of words, with a parent WordAdder component that lets you click a button to add a word to the list. This code does not work correctly:

class ListOfWords extends React.PureComponent {

render() {

return <div>{this.props.words.join(',')}</div>;

}

}

class WordAdder extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

words: ['marklar']

};

this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this);

}

handleClick() {

// This section is bad style and causes a bug

const words = this.state.words;

words.push('marklar');

this.setState({words: words});

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<button onClick={this.handleClick} />

<ListOfWords words={this.state.words} />

</div>

);

}

}

The problem is that PureComponent will do a simple comparison between the old and new values of this.props.words. Since this code mutates the words array in the handleClick method of WordAdder, the old and new values of this.props.words will compare as equal, even though the actual words in the array have changed. The ListOfWords will thus not update even though it has new words that should be rendered.

The Power Of Not Mutating Data #

The simplest way to avoid this problem is to avoid mutating values that you are using as props or state. For example, the handleClick method above could be rewritten using concat as:

handleClick() {

this.setState(prevState => ({

words: prevState.words.concat(['marklar'])

}));

}

ES6 supports a spread syntax for arrays which can make this easier. If you're using Create React App, this syntax is available by default.

handleClick() {

this.setState(prevState => ({

words: [...prevState.words, 'marklar'],

}));

};

You can also rewrite code that mutates objects to avoid mutation, in a similar way. For example, let's say we have an object named colormap and we want to write a function that changes colormap.right to be 'blue'. We could write:

function updateColorMap(colormap) {

colormap.right = 'blue';

}

To write this without mutating the original object, we can use Object.assign method:

function updateColorMap(colormap) {

return Object.assign({}, colormap, {right: 'blue'});

}

updateColorMap now returns a new object, rather than mutating the old one. Object.assign is in ES6 and requires a polyfill.

There is a JavaScript proposal to add object spread properties to make it easier to update objects without mutation as well:

function updateColorMap(colormap) {

return {...colormap, right: 'blue'};

}

If you're using Create React App, both Object.assign and the object spread syntax are available by default.

Using Immutable Data Structures #

Immutable.js is another way to solve this problem. It provides immutable, persistent collections that work via structural sharing:

- Immutable: once created, a collection cannot be altered at another point in time.

- Persistent: new collections can be created from a previous collection and a mutation such as set. The original collection is still valid after the new collection is created.

- Structural Sharing: new collections are created using as much of the same structure as the original collection as possible, reducing copying to a minimum to improve performance.

Immutability makes tracking changes cheap. A change will always result in a new object so we only need to check if the reference to the object has changed. For example, in this regular JavaScript code:

const x = { foo: "bar" };

const y = x;

y.foo = "baz";

x === y; // true

Although y was edited, since it's a reference to the same object as x, this comparison returns true. You can write similar code with immutable.js:

const SomeRecord = Immutable.Record({ foo: null });

const x = new SomeRecord({ foo: 'bar' });

const y = x.set('foo', 'baz');

x === y; // false

In this case, since a new reference is returned when mutating x, we can safely assume that x has changed.

Two other libraries that can help use immutable data are seamless-immutable and immutability-helper.

Immutable data structures provide you with a cheap way to track changes on objects, which is all we need to implement shouldComponentUpdate. This can often provide you with a nice performance boost.